Exploring Oxford’s Connections to Slavery through Portraiture

This blog post is written by Kristine Guillaume (MSt Intellectual History, Balliol) and Xaira Adebayo (BA History, Pembroke). Kristine and Xaira, together with Feyidara Olawuyi, were student interns on the History Faculty’s first internship scheme with ACKHI and the Museum of Oxford.

Junie James (ACKHI) and Kate Toomey (Museum of Oxford) designed the project, ‘Revelations: Black History in Portraiture’, to research Oxfordshire’s Black History connections through the portraiture collections of the University’s Exam Schools and the Town Hall on St Aldates. This project aimed to explore the nature of legacies of empire and slavery connected to the networks of wealth that are embodied in the portraits of prominent individuals displayed in these two key institutional spaces. In a twist on the struggle between ‘Town vs. Gown’, this project delved into connections of power and wealth that run between the city and the university, and historically spread further across the county, nation and empire.

Kristine and Xaira here present their reflections about working this project; as well as providing biographical sketches of some of the most interesting historical characters covered by their research.

It’s no secret that many of Oxford’s spaces – both in the university and the city at large – are adorned with portraits of dead white men. The images that hang in these places speak volumes about Oxfordshire’s history as they depict members of Parliament, venerated alumni of the university, and royal figures.

The ‘Revelations’ project contends that art can offer insight into who held wealth and power in the United Kingdom throughout the last several centuries, and examines how that is reflected in portraiture in Oxfordshire. As that power and wealth was accumulated during the rise of the British empire, the figures depicted in these portraits often have substantial ties to the transatlantic slave trade and imperialism. This project investigates those depicted in Oxford’s Town Hall and the Examination Schools to better understand the city and university’s links to Atlantic slavery.

There are over 100 portraits in the Examination Schools and in the Town Hall, meaning that our study of these portraits over the course of four months likely only scratched the surface of possible links to slavery and imperialism. We approached our research through examining four themes: (1) profits generated from enslavement or enforced labour within the British Empire and its colonies, (2) broader familial ties to enslavement in the Caribbean or profits generated in the slave trade, and (3) identifying any leadership positions or organizational memberships held that might suggest investment — financial or otherwise — in the slave trade. The scope of this project focuses on links to the Americas, but there are many other portraits of figures who had more influence in other sites of imperialism such as India and South Africa.

The study of these portraits offered an interesting methodological approach to explore the interconnections of the transatlantic slave trade and colonialism. Power and wealth concentrated in property are central sites of ties to commerce and slavery, and the country’s elite, intellectual class certainly contributed to the culture and framework that sanctioned slavery and imperialism in the United Kingdom.

In doing this, we acknowledge that this is not the first study of its kind. Balliol College, the Rhodes Must Fall movement, and independent researchers such as Anne Avery and Junie James have all traced the university and city’s ties to the slave trade and imperialism. The investigation into portraiture illuminates the need to continue to historicise and contextualise the place the university and Oxfordshire occupy in the collective and national memories of the transatlantic slave trade; as well as coming to terms with the fact that the space that the institution occupies/has constructed is a material legacy of empire and slave-trading.

In what follows, we provide biographies of some of the figures in Oxford’s portraits, who illustrate the explicit and implicit connections between Oxfordshire and the slave trade.

George Spencer, 4th Duke of Marlborough—Oxford Town Hall Assembly Room

Born in 1739, George Spencer – of the well-known Spencer and Churchill families in the United Kingdom – is the great-great-great grandfather of Sir William Churchill. Spencer resided at Blenheim Palace, where he eventually died in 1817.

Spencer is a descendant of John Churchill, the 1st Duke of Marlborough, whose daughter, Lady Mary Churchill, is depicted in a 1720 portrait with a Black servant named Charles Ignatius Sancho; the portrait currently resides at Boughton House in Northamptonshire. Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, depictions of Black domestic servants in great houses and estates were viewed as signs of wealth and power. In addition, Elizabeth Spencer—one of George Spencer’s eight children—married John Spencer (a son of Charles Spencer, the 3rd Duke of Marlborough), who enslaved a Black man named Caesar Shaw in the eighteenth century. Shaw is featured in two portraits at Althorp House in Northampton. These portraits in the Spencer family’s holdings history signal a link between one of Oxfordshire’s wealthiest families and the slave trade, especially as images of Black domestic servants were a means of communicating their status and wealth. The 12th Duke of Marlborough resides at Blenheim Palace today.

George Spencer, 4th Duke of Marlborough—Oxford Town Hall Assembly Room

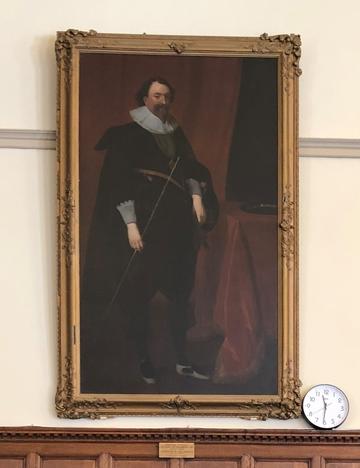

William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke—Examination Schools, North Schools

William Herbert, as the Earl of Pembroke, is the namesake of Pembroke College, which was founded in 1624 by King James. At the time, Herbert acted as the Lord Chamberlain and Chancellor of the University of Oxford. Herbert was also an investor in the Guiana Company, Somers Island Company and the East India Company. His 1612 investment in the Virginia Company regarding its third charter for the colonisation of Bermuda establishes a tentative link between Pembroke College and the early British empire - though it is difficult to exactly decipher Herbert’s monetary stakes in the company, due to missing financial records and omissions. According to St Hugh’s College archivist, Amanda Ingram, who previously worked at Pembroke, Herbert died ‘suddenly and and intestate, in 1630 before making any donations to the College and his estate passed to his brother, Philip’. Though Herbert himself did not make any donations to Oxford, his legacy still marks a prime example of the connections between the University and the slave trade.

William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke—Examination Schools, North Schools

William Henry Cavendish-Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland—Examination Schools, North Schools

William Henry Cavendish-Bentinck played an extensive role in the political management of empire; he served as home secretary, chancellor of the University of Oxford, and twice as prime minister of the United Kingdom, meaning his legacy holds significance both to Oxford and to the rest of the country.

Cavendish-Bentinck was a product of the 1% of the English landed elite who owned 20 to 25% percent of land in England in the eighteenth century. He was the manager and owner of Bolsover Castle, his family home from 1762-1795. Built in the seventeenth century, the property was later maintained by his family’s connections to the slave trade, particularly through proceeds generated by plantation holdings in the Demerara region of British Guiana, known as ‘La Bonne Intention’. Henry William Bentinck (1765-1820), Cavendish-Bentinck’s son, was directly involved in the management of this plantation. By 1808, Henry William and his brother Charles Ferdinand (Governor of Suriname, 1809-1811) each owned one sixth share in the property. The plantation is also known for the slave insurrection of 1823, an uprising involving more than 10,000 enslaved people.

Cavendish-Bentinck’s political career was defined by two cases pertaining to slavery and proprietorship: the Zong Massacre in 1781 and the Fedon Rebellion of Grenada in 1795. In the former, Granville Sharp—a prominent figure of the abolitionist movement—petitioned Cavendish-Bentinck to speak on the case. The case emerged after Captain Luke Collingwood of the Zong threw many sick enslaved, captive African people overboard his ship, to protect his profits in 1781. Collingwood made an insurance claim to minimize his losses, and the case — rather than being considered for act of murder — was considered in court proceedings as a matter of property. Cavendish-Bentinck remained silent on the matter. This silence has been inferred by the historian, David Wilkinson, as an indication of his position in matters of slavery and abolition to be one that defined enslaved people as property, rather than human beings.

His ideological position on this matter is further embodied in his political response to the 1795 Fedon Rebellion — an uprising against British rule instigated predominantly by the free people of colour in Grenada to create a Black republic. At the time, the uprising was described by British political contemporaries as ‘the most serious threat posed to British control anywhere in the Antilles’. The rebellion resulted in the loss of £2.5 million. 100 plantations were destroyed; 7,000 enslaved people were killed, injured or deported; and 50 British planters were executed. Liverpool merchants pressed Cavendish-Bentinck to expedite and review the process of recompense in these estates as local commissioners were felt to be doing an inadequate job – requests that have been deemed a response to his assumed stance regarding the centrality of proprietorship.

William Henry Cavendish-Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland—Examination Schools, North Schools

Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon—Examination Schools, Room 7

As Chancellor of the University of Oxford from 1928 to 1933, and a British Liberal statesman, Fallodon had definitive ties to the British empire as Foreign Secretary to Lord Kimberley (1905-1916), and through indirect relations to properties built and maintained through financial earnings from the slave trade. Fallodon was in office in the nadir of the new imperial state underpinned by the scramble for Africa, and he supported France in the Moroccan Crises of 1905 and 1911: a conflict between Franco-German powers to gain control of Morocco. Fallodon’s immediate support was a factor in the strengthening of the Anglo-French entente, an agreement which acted as an acknowledgement of occupations of Morocco (by France) and Egypt (by Britain).

Fallodon also inherited Stocks House, a Georgian mansion constructed in 1773, in 1891. The house had previously been owned by James Gordon, who inherited the property via marriage in the early nineteenth century. Gordon’s family had sizable plantation estates in Antigua, St. Vincent and St Kitts. Though Fallodon sold the house relatively soon after coming into its possessions, his connections to the slave trade through the building further illuminates a salient theme of the material legacies of the transatlantic slave trade on the English country house.

Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon — Examination Schools, Room 7

George III—Examination Schools, South School

King George III was head of the United Kingdom from 1760-1820; his reign, therefore, was marked by a dynamic, crucial period of transformation in the British empire with the Seven Years War with France and the American Revolutionary War. In the 1780s, George III wrote a letter on the loss of the American colonies, highlighting the wealth that had been generated for the United Kingdom from the sugar, rice, and tobacco colonies in the American South.

George III’s specific stances on slavery and imperialism, however, have been the subject of renewed critical discussion. Andrew Roberts, for example, has recently called for a re-examination of the king’s legacy. In an interview with The New Yorker, Roberts contended that figures like Thomas Jefferson and George Washington cannot easily be considered “better” figures than George III, as the king never “bought or sold a slave in his life”; did not invest in any of the slave trading companies; and signed the abolition of the slave trade into law in 1807. Roberts also references an essay that written by George in the 1750s, which called arguments for the practice of slavery “absurd”. In that essay, the young prince wrote that the laws of slavery are “contrary to the fundamental principles of all Society.” Roberts’ contention, however, seems to premise itself on a markedly narrow conception of what it meant to invest and profit from the slave trade, seemingly discounting the royal family’s enormous implication in empire and George III’s concern with the wealth of the colonies—which relied on slavery to maintain this wealth—a key theme documented in the archives.

Drawing from his aforementioned writings and other contemporaneous letters, the loss of wealth via the loss of colonial possessions very much concerned the king. In September 1779, he ordered the dispatch of more troops to secure Barbados and Jamaica, writing: “Our Islands must be defended even at the risk of Invasion of this Island” and “if we lost our Sugar Islands it will be impossible to raise Money to continue the War and then no Peace can be obtained.” George III’s son, Prince William, the Duke of Clarence, was an ardent defender of slavery and member of the Royal Navy who travelled to the Caribbean. While George III eventually approved the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, he and his son supported efforts of the London Society of West India Planters and Merchants to delay the abolition of the slave trade for nearly 20 years.

George III — Examination Schools, South School

Some reflections on future directions for the project

In our inquiry, we explored proprietorship in some individuals, but many questions remain in terms of English estates, country houses, and academic buildings as commercial legacies of the slave trade. To what extent is Oxford’s architectural topography shaped by the commodification of human life?

In terms of the physical materials used for this research, it was often quite difficult to navigate the journey of the paintings to Oxford. Further work is thus needed to uncover the circumstances through which these images ended up in the University and Town Hall collections.

We are also aware that this project has been a somewhat masculinist endeavour, as the vast majority of portraits from the period depict white men. This foregrounds further questions on the centrality of connections of empire and slavery to androcentric social and political power, though this is not to establish a narrative that empire and transatlantic slave trade was solely a male-driven project (as was mentioned above, for example, Lady Mary Churchill is also depicted in a portrait at Blenheim Palace with a Black servant). Future questions in this inquiry could therefore explore women’s ties to slavery and imperialism in Oxfordshire.