Taking part in the ‘History of Muslims in Oxford’ project

Mohammed Alam Begi

This post is written by Mohammed Alam Begi, who graduated with his BA in History in 2012. Mohammed was one of the first interns on the Faculty’s Community History initiative, working on the collaborative project, ‘The History of Muslims in Oxford’ together with our community partner, Everyday Muslim. He will soon be commencing a Masters’ course at Harvard University.

It was a real privilege to have been a part of the ‘History of Muslims in Oxford’ project with the History Faculty at the University of Oxford. Engaging in this kind of research was an exciting opportunity that allowed me to put the skills that I developed as an undergraduate historian into practice. It is also an exciting opportunity for the History Faculty to engage with and hear the stories and record the lived experiences of individuals who call Oxford their home. The Faculty should continue to deepen its links with the local community and offer students and researchers opportunities to explore the fascinating history of Oxfordshire and its people.

To conduct my research, I used oral history interviews. Oral sources have long been central to the work of historians. Paul Thompson, one of the recent pioneers of oral history as a research method, mapped out the use of oral sources back to Ancient Greece. Thus, while there is an ongoing and lively debate among historians about the subjectivity and reliability of oral sources; it is notable that such ancient works as the History of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides, the 8th century History of the English Church and People by Saint Bede and Jules Michelet’s History of the French Revolution have all, to a certain degree, relied on the use of oral testimonies.

When I was offered a research internship by the Faculty, I started looking for potential participants to interview for my research. Earlier, in September 2021, I had accompanied a group of Afghan refugees as a charity volunteer to Friday prayers at the Medina Mosque in Cowley. Sadat Khan, a member of the Muslim community in Oxford, was also at the prayer. Sadat made an announcement to the congregation and urged the community to support the resettlement and integration of the new refugees into the community. Outside the mosque, I had a brief conversation with him and discovered that he was the Chairman of Madina Mosque and the co-founder of Royal Cars, a prominent taxi company in Oxford.

Given his connections to Oxford’s Muslim community, I thought Sadat would be a fantastic candidate to interview. He agreed to be interviewed and invited me to the offices of Royal Cars. This article explores parts of Sadat’s journey and lived experiences.

Sadat was born in Waisa, a small village in the Chhachh Valley, Pakistan. In 1958, his father came to Oxford as an economic migrant. Sadat joined his father in 1965. His education was disrupted as he moved between Oxford and Pakistan during his childhood. In Pakistan, he spent most of his time at the family farm. Sadat attended Iffley Academy in Oxford. As one out of the two non-white students in his school, he would be called names. When I asked how he dealt with racism, Sadat said, ‘you just take it in.’ Sadat spoke fondly about his friendship and memories with his neighbours, Steven, and Lawrence. They played football near Donnington Bridge.

As the oldest son in his family, Sadat had to shoulder the responsibility of providing for his family when he turned sixteen. His first employer was Nuffield Orthopaedic Centre, where he was paid £18 a week for 40 hours of work. He told me, ‘Not many 16-year-olds have to go and fend for themselves, but I had to do that.’ In his early twenties, he ran a youth club in East Oxford and campaigned to convince Oxford County Council to create a football pitch in his area. As more Pashtuns settled in Oxford, he helped to set up the Oxford Pashtun Foundation, which he is currently chairs.

He identifies himself as a ‘fully Western’ and ‘fully Pashtun’ individual. He believes that he has integrated into the community and has remained connected to his culture and identity. However, Sadat has anxieties about the identity of the generations that succeed him. His grandchildren can speak a few words of Pashto here and there. Language is an important part of identity for Sadat, because ‘once you lose your culture and your language, you lose your identity.’

My interview with Sadat brought important historical moments and themes to life. His journey to Oxford for instance, has a lot to do with the consequences of British imperialism and post-war Britain. As a minority, his childhood experiences in Oxford opens a window into poverty, social mobility, and equality. As an adult, his lived experiences can offer a unique perspective on community, identity, and entrepreneurship.

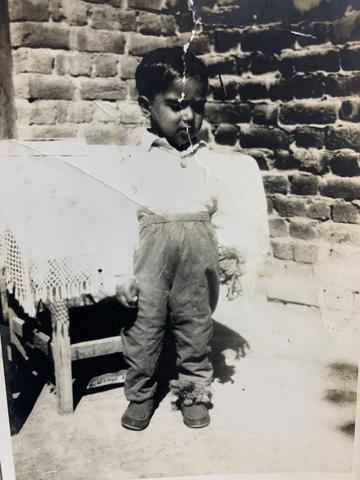

Sadat Khan when he came to the UK

Sadat’s family