Wytham History and Community Project

Wytham History and Community Project

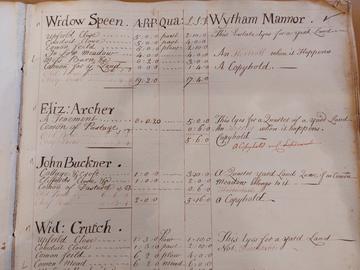

detail about tenants on the Wytham estate, from Oxford, Bodleian Libraries, MS. Top. Oxon. c. 381, courtesy of the Bodleian Libraries

When I was invited to join the Wytham Histories and Communities project, I had little idea of what it would entail. In particular, I was onboarded to research the Wytham Estate in the 18th and 19th centuries, and to compare how it was run to other similar estates in the region. I had some previous experience with the Oxford University Museum of Natural History and the Museum of Oxford on a variety of historical topics (see the note below). However, I had never gone through the process of identifying and extracting information from manorial and estate records. The experience of accessing these documents felt surreal - I requested the items from Special Collections at the Bodleian via an online portal and soon enough I was holding these centuries-old documents in my own hands!

In the past few months, I have been reading about the Wytham Estate and other comparable estates. In the 18th and 19th centuries the Berties, the Earls of Abingdon were lords over Wytham, until the estate was sold to the ffennell family in 1920. The estate first came into the possession of the Berties via Montagu Bertie’s marriage to Bridget Wray, of Norreys descent, in 1658. Their son James was made the 1st Earl of Abingdon after his service to Charles II. The first earl to actually live on the estate was Willoughby Bertie, the 4th Earl of Abingdon, before then the principal seat of the family being Rycote

near Thame, or sometimes they resided in London. Perhaps this is why up until the 4th Earl decided to move the residence of the family to Wytham, little effort was made to improve how the estate was run. He was involved in turnpiking the road over Wytham Hill to Eynsham from Botley causeway and funded the development of the Swinford Toll Bridge. During his tenure he only began the process of enclosure by quartering some open field in nearby Cumnor, which the family also owned. His son, Montagu Bertie, the 5th Earl of Abingdon, who succeeded him in 1799, was much more interested in improvement and funded the remodelling of Wytham House, rebuilding of the church, bettering the landscape, and building a new road between Botley and Swinford.

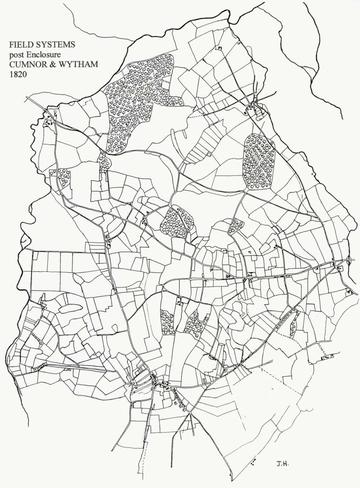

Wytham Cumnor Field System c1820 Reconstruction by John Hanson

One of the first tasks that I undertook was transcribing manorial records of various leases in Wytham, Seacourt and Cumnor. One of the first challenges that I encountered was understanding the types of leases and tenants in the post-medieval period. I was pleased to discover a very helpful recent study of a neighbouring village. As Richard Dudding explains in Radley Manor and Village: A Thousand Year History (Radley History Club, 2019), there were two main types of tenants of the manor: freehold tenants and customary tenants. Freehold tenants are, as one might expect, owners of the property, and they were not subject to the customs of the manor. Customary tenants are divided into two types, the first of which is cottagers, who would hold between 3-4 acres of land, had restricted rights to commons, and usually had to provide some sort of paid labour to the lord of the manor. The second type would hold a ‘messuage’ which would usually entail a farmstead with a virgate of land (a virgate being about 30 acres). It should be noted however that one tenant could hold several messuages, virgates and cottages within their holdings.

Customary tenants were granted access to land via ‘copyholds’, a type of land ownership where the tenants were given a copy of the manorial roll stating their status as copyholders. Copyholds could be inherited or passed down to widows, as exemplified by

one Mary Tyrell/Tyrill in ‘her Widows Estate according to the custom of the Mannor aforesaid by virtue of a Copy of Court Roll granted thereof to her late Husband’, described in a 1740 lease document between John Westbrooke on her behalf and Montagu Bertie (the second Earl) for a messuage and ‘two and a half yard’ worth of land in Wytham. Copyhold tenants were also subject to a ‘heriot’ or tax placed on new tenants upon the previous tenant’s death. We know from the Bertie family archives in the Bodleian that tenant records would include within their descriptions that they were subject to ‘An Herriott when it happens’ or classed as either ‘Herriotable’ or ‘Not Herriotable’. Most tenants in Wytham manor would have been yeomen copyholders, with no leaseholds present in 1730.

The husbandry practiced in Wytham was governed by the manorial system. Manor documents indicate that the land management was carefully considered and rules were put in place to maintain it to a good standard. For example, within the Court Rolls of the Manor of Wytham for 1720 - 1753 it is revealed that ‘None shall put above Eight horses or Cows upon One Yard Lands Common and Cattle to be marked by fieldmen’, the penalty for not adhering to this being one pound (around £174 in today’s currency). However the system in place was increasingly felt to be disadvantageous for multiple reasons: distributing land ‘fairly’ with a variety of good and bad soils and land meant inefficiency due to distance being travelled; constant contention on where boundaries were due to their excessive length; reliance on ‘tradition’, which impeded experimentation and improvement; co-operative livestock management, with crop damage from failure to maintain ditches and many disputes being caused by breaking of common grazing rules.

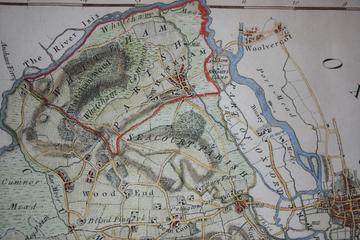

Wytham on John Rocque's map of Berkshire, 1761

Robert Whittleray (1728) in his comments on Wytham’s husbandry practice suggested that it had potential for improvement if the fields were fallowed appropriately, if the tenants reduced the number of livestock allowed to graze on the common meadows, and if ‘wasted land’ were to turn into private property. Comparatively close by, in Radley, there was more experimentation and improvement happening at the time. They followed the example of Jethro Tull from nearby Wallingford, who modernised farming, by inventing a drill that would enable seeds to be sown in straight rows. He made other farming improvements, particularly in ploughing, by experiments with new root crops for the winter which prevented having to slaughter livestock each autumn. This resulted in breeding better stock and made fresh meat available year-round.

The prevalence of mixed farming due to the nature of the manorial system, local geology and the needs of the city population protected tenants from the consequences of poor husbandry at Wytham. Whittleray’s recommendations for improvement were enclosure, limitations to common grazing rights and soil improvements, but these were not taken on at the time. Proper enclosement only occurred in the first half of the 19th century by the 5th Earl of Abingdon, as enclosure via Parliamentary Acts was taking place. In my next blog I will discuss enclosure and its consequences more at length.

Iulia Costache

Iulia works full time as a Monitoring & Evaluation Consultant and is now engaged in a history internship for the Wytham Histories and Communities project looking at the 18th and 19th centuries of the Wytham Estate. She is passionate about community history and storytelling, having volunteered for the Museum of Oxford writing short historical blogs and for the Oxford Museum of Natural History transcribing 18th & 19th century letters between naturalists.